Perfluorinated or polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of more than 4,700 synthetic chemicals. Their ubiquitous persistence in the environment and exposure to humans since the 1940s have been a public health concern due to their documented negative impact on health.

PFAS are found in everyday appliances like waterproof coating, food packaging and non-stick cookware. These chemicals leak into the environment during manufacturing, use and disposal and contaminate the water, soil, air and living organisms. PFAS are commonly referred to as ‘forever chemicals’ because their molecular structure makes them highly resistant to being broken down.

One of the more recent areas of research in the PFAS space is based on its link to increased diabetes risk. A recent contribution to Diabetologia by Park and colleagues sought to examine the link between PFAS and diabetes in women. Study findings observed an increased risk of developing diabetes, which suggests that PFAS may be an important diabetes risk factor to monitor over the next ten years.

In the study by Park and colleagues, the relationship between types of PFAS exposure at different levels and the risk of developing diabetes was quantified in women aged 45–56 years. The study, conducted by the University of Michigan School of Public Health’s Department of Epidemiology, enrolled 1,237 non-diabetic women at the baseline year (1999–2000) from seven US sites in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN-MPS). The sample was clinically assessed annually until 2017 and repository serum and urine samples were collected to quantify environmental PFAS exposure.

The serum concentrations of seven types of PFAS compounds were chemically tested for and categorised into high, medium and low exposure groups. The 102 women who developed diabetes had higher serum concentrations of certain types of PFAS compared with the women who did not. More specifically, study participants who were exposed to all seven PFAS compounds in the high category were 2.62 times more likely to develop diabetes than those in the low category.

PFAS chemicals act similarly in the human body to naturally occurring fatty acids due to their similar molecular structures and chemical properties. Fatty acids act on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), a class of proteins that play a key role in regulating the production of new fat cells (adipocytes) and controlling fat and glucose levels. Exposure to high levels of PFAS that are structurally similar to fatty acids could potentially interact with the same PPARs and disrupt the physiological pathways, leading to increased fat cell production and changes in fat and sugar metabolism.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

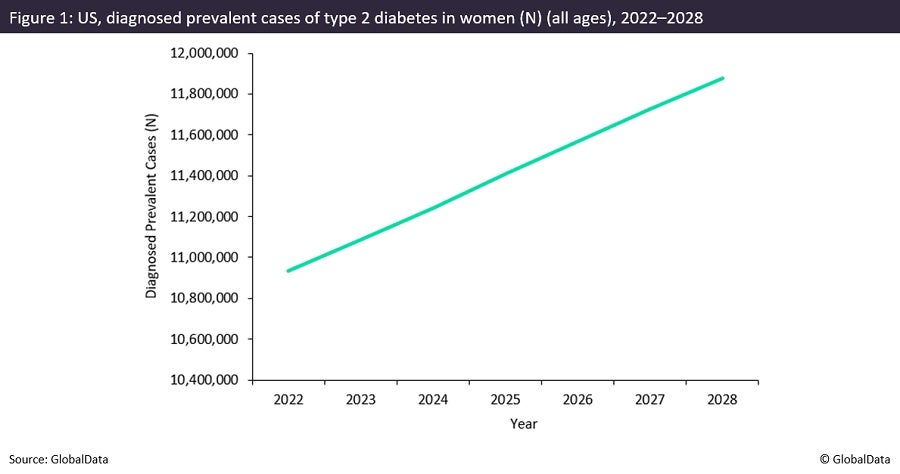

By GlobalDataGlobalData epidemiologists estimate there will be more than ten million diagnosed prevalent cases of women with type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the US by the end of this year. That number is predicted to increase to nearly 12 million diagnosed prevalent cases by the end of 2028 (as shown in Figure 1). But if PFAS continue to increase in the environment and no public health mitigation measures are put in place, the diagnosed incident cases of T2D may surpass current forecast estimates.

These findings show that PFAS exposure may be a potential risk factor for diabetes in women. Reducing the contamination of these chemicals in the environment and introducing screening protocols could be a key preventative approach to reducing diabetes risk. Some European countries have already taken steps forward and officiated regulations on PFAS use and manufacturing.