Researchers at the University of Birmingham have identified a new type of immune cell that can fight viral infections.

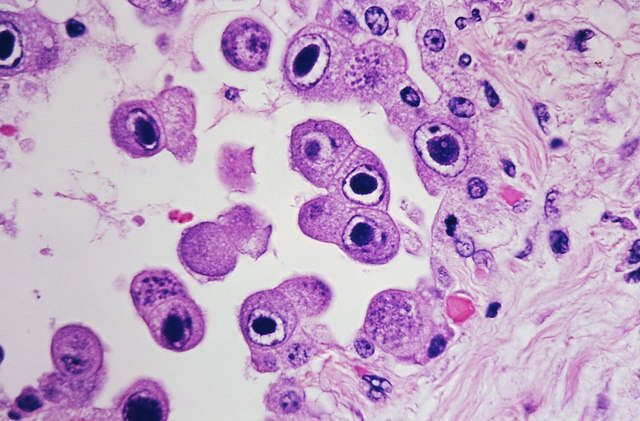

The immune cell under examination is a subset of unconventional V-delta-2 lymphocytes, a type of Gamma Delta T cell that until now has been relatively unexplored. The recent study found this subtype to be present at birth and to persist throughout adulthood, albeit at low levels. However, these levels were shown to increase following viral infection.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

In the study, the researchers examined how this subtype responded to a cytomegalovirus infection. They found that when these T cells detected signs of the infection they increased in numbers and became aggressive.

“These cells can clearly adapt to some key challenges that life throws at them,” lead author Dr Martin Davey said.

“Upon viral infection, they change from harmless precursors into what appear to be ruthless killers.

“They can then access tissues, where we believe they detect and destroy virally infected target cells.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe study follows previous work conducted by the same group, which implied many gamma delta T cells that control our immune system can adapt when facing infection. Findings were published last month in Trends in Immunology.

The research team is now attempting to discern the situations in which these T cells are most important and whether they can be used for future viral infection treatments.

“We think these cells contribute to defence against viral infection in the liver, a site which is exposed to many potentially dangerous infectious diseases,” Davey said.

“They may also be particularly important when other aspects of our immune system are not working at full strength, such as in newborn babies, but also in transplant patients who are taking immunosuppressive drugs to prevent organ rejection.

“In these scenarios, boosting the activity of these cells could prove beneficial to patients, and we are now starting to explore how to do that.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Academic Medical Center in the Netherlands and the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology in Russia, with findings published in Nature Communications.