The growing prevalence of opioid use disorder in North America has become a public health crisis, necessitating novel policy solutions to reduce its impact.

Among the most controversial solutions is the practice of supervised consumption services (SCS), in which individuals who use drugs may do so under the supervision of trained professionals providing a safe venue for the use of prescreened substances.

While advocates propose that SCS is an effective means of harm reduction, few governments have adopted it.

In a recent publication in The Lancet Public Health, Rammohan and colleagues explored the impact of SCS on drug overdose mortality in Toronto, Canada, which has utilised SCS facilities since 2017.

Their analysis indicates that SCS reduced overdose mortality in nearby neighbourhoods, suggesting its effectiveness in combatting drug overdose deaths.

In Canada, GlobalData (a leading data and analytics company) epidemiologists forecast an increase in the diagnosed prevalent cases of opioid addiction from more than 184,000 in 2024 to over 185,600 in 2028.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWhile SCS is a nascent policy solution to this growing crisis, further research supporting Rammohan and his colleagues’ conclusions may build a case for its adoption, potentially impacting these dynamics.

Rammohan and colleagues carried out an ecological study and spatial analysis of SCS impact on overdose mortality across all of Toronto starting shortly before SCS implementation in 2017 and ending in 2019.

During this period, municipal records listed 787 drug overdose mortalities, the majority of which were opioid-related.

The authors analysed these deaths with a focus on the distance between decedents’ postal codes and SCS facilities.

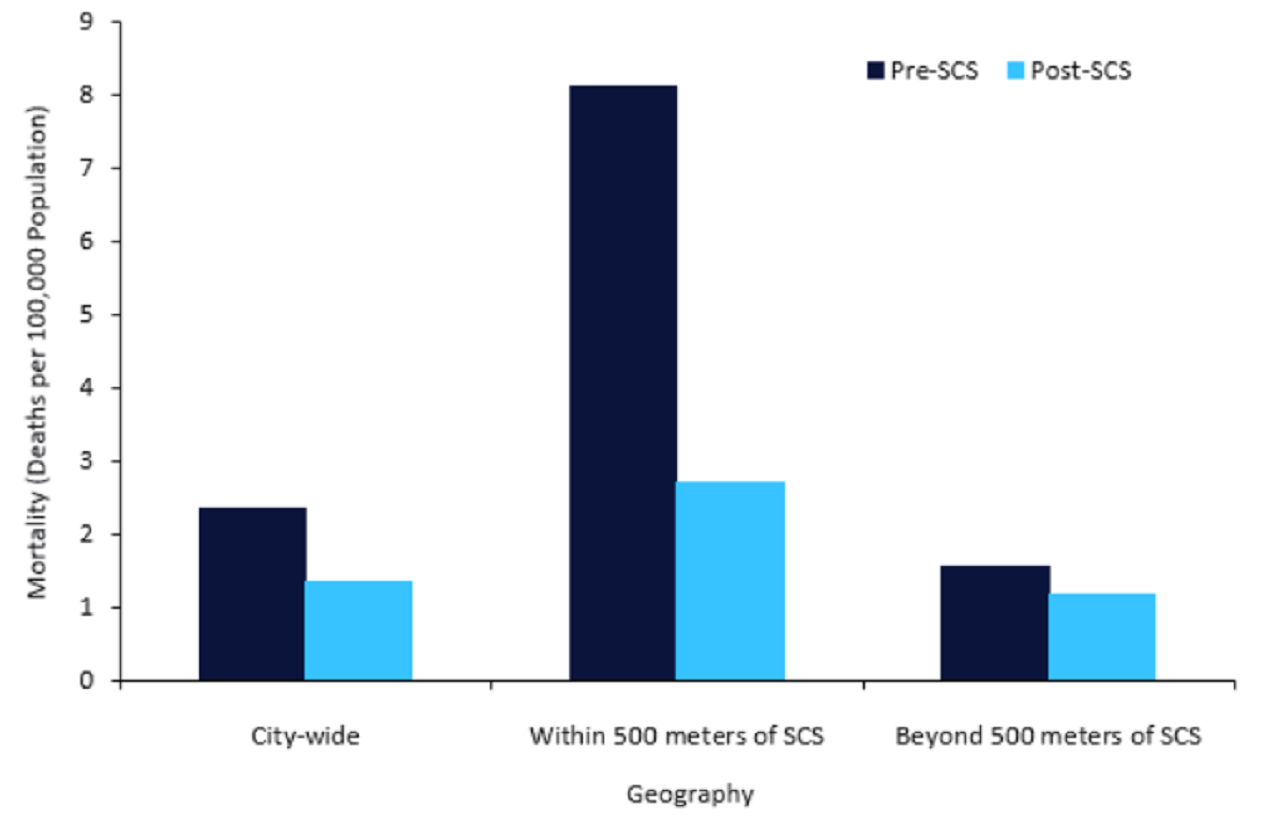

Results indicated a citywide reduction in overdose mortality from 2.34 cases per 100,000 population to 1.35 cases between the pre-SCS and post-SCS period (Figure 1).

In neighbourhoods within proximity of 500m from an SCS facility, mortality fell from 8.10 to 2.70 cases per 100,000 population.

While mortality also decreased in neighbourhoods beyond 500m of a facility, the effect was a modest reduction in mortality from 1.54 to 1.17.

The authors posit these relationships can be explained by increased access to overdose prevention measures and less stigma surrounding drug use in these settings, which enables greater engagement with safer drug use options.

These changes may introduce downstream effects in areas outside of SCS proximity via increased distribution of overdose prevention treatment such as naloxone.

The results and analysis of Rammohan and colleagues’ study present a promising avenue for policymakers attempting to mitigate the worst effects of the opioid crisis.

However, the use of SCS faces limitations that require further inquiry.

A notable barrier to SCS is the persistent societal stigma surrounding illicit drug use, which could hinder legislation due to public perceptions that SCS enables or encourages criminal behaviour.

Moreover, SCS in its current state appears to be an effective means of saving lives but does not address the underlying epidemic of drug addiction itself.

In order to address these pitfalls, it is imperative for health professionals and policymakers to further research the efficacy of SCS and determine its role within a larger suite of approaches to combatting the foundational drivers of addiction.