For several years, public health experts have identified the opioid addiction crisis as a leading cause of the US’s unprecedented decline in life expectancy. While high rates of opioid use disorder (OUD) have been observed in various parts of the country, its effects have been amplified among communities with lower socioeconomic status (SES). In the US, these patterns may be exacerbated by a lack of medical coverage and stress associated with economic instability. In a recent publication in the Journal of the American Health Association Health Forum, Paul J Christine and colleagues explored the interplay of OUD and insurance instability in the US. Their analysis, which suggests that OUD patients experienced a higher rate of insurance transitions, highlights the complex interplay between SES, cognition, and opioid addiction. GlobalData epidemiologists project that the diagnosed prevalent cases of opioid addiction will increase from nearly 1,050,000 cases in 2024 to approximately 1,070,000 cases in 2028. In response to these worrying trends in the opioid epidemic, sensitivity to the socioeconomic backgrounds and insurance status of the patient population will prove critical to a successful reduction in addiction rates.

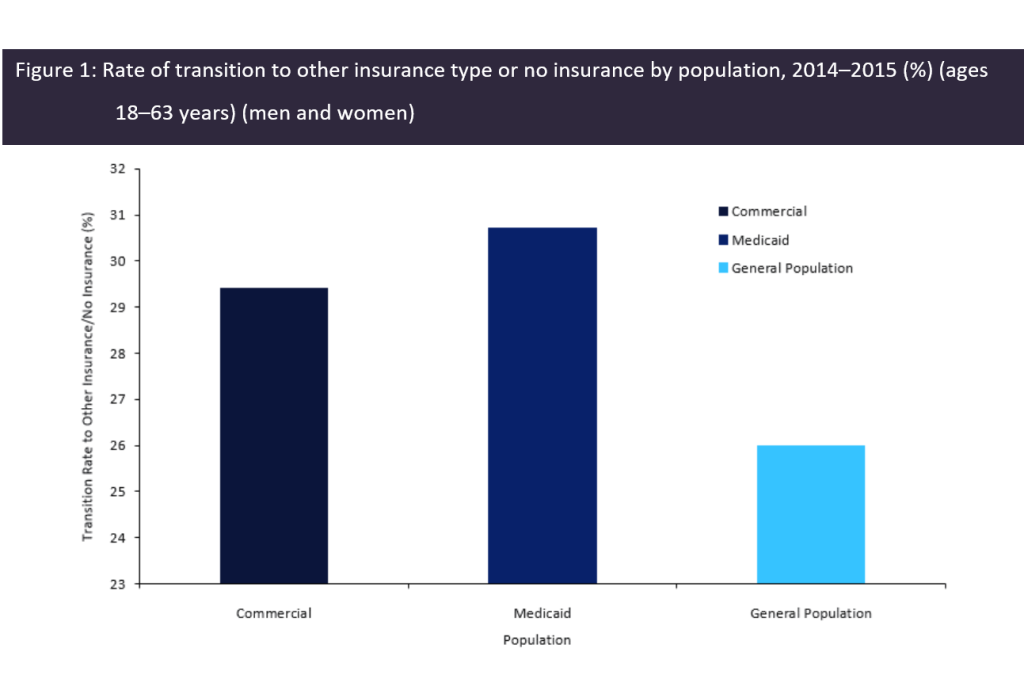

To observe the effects of insurance gaps and transitions on OUD patients, Christine and colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study through analysis of the Massachusetts Public Data Warehouse, a pooled database of the state’s medical claims, between 2014 and 2015. Payers aged 18–63 years who were recorded in the database were selected based on medical coding for OUD-related illnesses within 180 days of the claim, yielding 20,768 cases. The study cohort was then segmented by insurer type into Medicaid or commercially insured populations. The OUD claims of each population were observed for evidence of an insurance transition, which the authors defined as a change from the insurance type at the study’s outset to a different type. The analysis revealed that among all patients, 29.4% of the commercial insurance population and 30.70% of the Medicaid population saw a transition in insurance within one year of their first OUD diagnosis, exceeding the average transition rate of 26% observed in the Massachusetts general population (Figure 1, below). Incidence patterns showed that the most common insurance transition event was commercial insurance to uninsured at 24.4%, followed by Medicaid to uninsured at 16.7%. When segmented by race, insurance transition was significantly higher among OUD patients who were younger and belonged to historically disadvantaged racial minorities.

The implications of Christine and colleagues’ analysis suggest a self-reinforcing pattern between insurance status and OUD diagnosis. The higher propensity for insurance transitions among OUD patients may exacerbate their ability to receive care, thereby increasing their risk of addiction morbidity and potential overdose mortality. Furthermore, adverse life events such as losing employment and healthcare coverage may drive further opioid abuse as a coping mechanism, especially among individuals who transition from commercial insurance to having no insurance. In turn, those without insurance may lose access to addiction treatment services. This interaction perpetuates a “vicious cycle” of job precarity among OUD patients, contributing to and fed by reliance on opioids in response to stress. As public health authorities, physicians, and policymakers weigh responses to the opioid crisis, it is critical to implement interventions that take into account the socioeconomic and cognitive factors underlying addiction, especially in the context of a healthcare system without universal health insurance coverage.