FDA-Approved Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Alzheimer’s

With Eli Lilly’s donanemab and Biogen’s aducanumab jockeying for position in the race for key regulatory approvals, the so-called amyloid hypothesis is being put to the test again after a string of trial failures. Could an amyloid-targeting therapy finally be poised for approval?

Finding an effective, disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease is one of the holy grails in drug development. No effective, approved treatment has come to market for the devastating neurodegenerative disease in 18 years, representing a huge unmet need.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Two companies in the race to meet this need are Biogen and Eli Lilly, both developing high-profile drug candidates based on the much-debated hypothesis that beta-amyloid plaques are the cause of Alzheimer’s.

The amyloid hypothesis

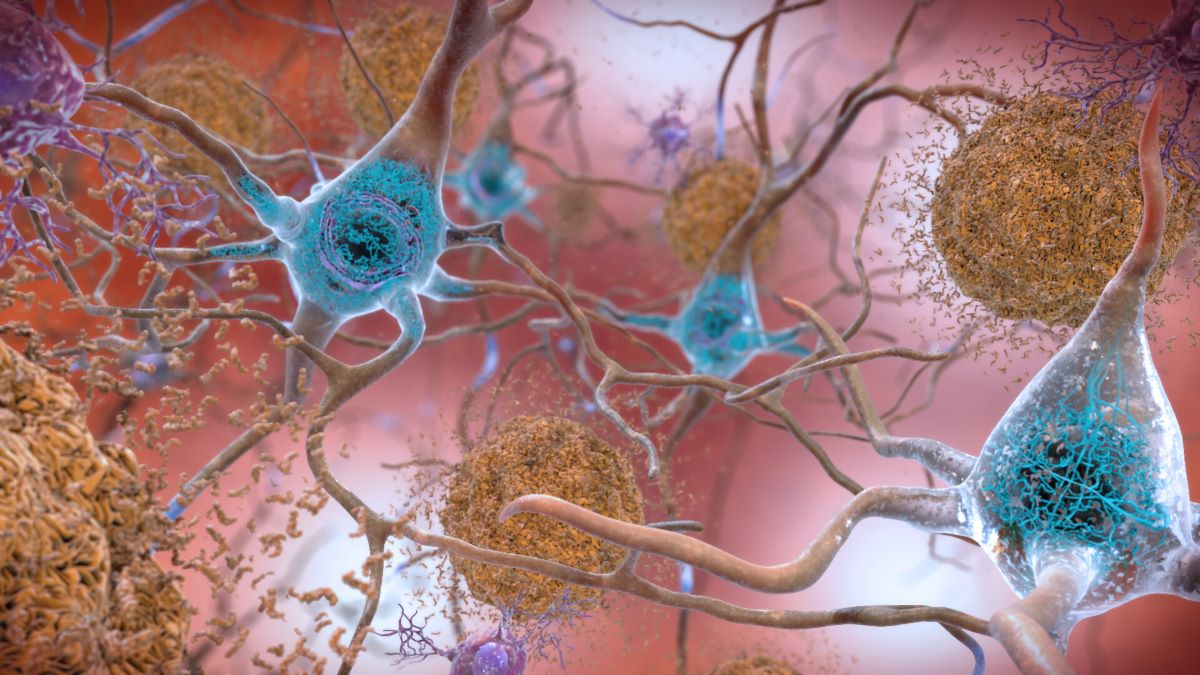

In Alzheimer’s disease, brain cells that process, store and retrieve information degenerate and die. Although scientists are unclear on the exact underlying cause of this disastrous death of cells, they have identified several prime suspects.

One of these is a microscopic brain protein fragment called beta-amyloid, a sticky compound that accumulates in the brain, disrupting communication between brain cells and eventually killing them.

Some scientists believe that defects in the processes dictating production, accumulation or disposal of beta-amyloid are the primary cause of Alzheimer’s – the so-called ‘amyloid hypothesis’.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBeta-amyloid is a tiny fragment of a larger amyloid precursor protein (APP), which in its complete form extends from the inside of brain cells to the outside by passing through the cell wall’s fatty membrane. When APP is “activated” to function normally, it is cut by other proteins into smaller pieces that stay inside and outside cells. Under some circumstances, one of the pieces produced is beta-amyloid.

Chemically stickier than other fragments produced when APP is cut, beta-amyloid accumulates in stages into microscopic amyloid plaques that are considered a trademark of an Alzheimer’s-affected brain. According to the amyloid hypothesis, these stages of beta-amyloid aggregation disrupt cell-to-cell communication and activate immune cells. These immune cells trigger inflammation which ultimately destroys the brain cells. But is this process the right target for the development of disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s? With a track record of clinical trial disappointments, the jury is still out.

But GlobalData neurology analyst Alessio Brunello, who attended the 15th International Conference on Alzheimer’s & Parkinson’s Diseases (AD/PD 2021) last week, notes that beta-amyloid remains “a very valid target for therapies in the future.”

“There is a long list of failed Phase III trials and these cast doubts about the approach of targeting beta-amyloid as a primary cause of Alzheimer disease,” says Brunello. “Some studies have indicated that the main factor in the development and progression of the disease is associated with tau [strings of a protein known to be another hallmark of Alzheimer’s] and not beta-amyloid. However, the amyloid hypothesis remains central in the development of anti-Alzheimer’s disease drugs.”

Lilly’s donanemab: approval uncertain after mixed Phase II results

Lilly’s drug Donanemab targets a type of beta-amyloid known as N3pG, which the firm believes can be rapidly cleared, enabling short-term but durable treatment.

On 13 March at AD/PD 2021, Lilly presented results from its Phase II TRAILBLAZER-ALZ study, which included 257 subjects. The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

131 patients were assigned to receive donanemab and 126 received a placebo.

Full data from the clinical trial show that patients on donanemab experienced a 6.86 decline in scores on the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (iADRS) while scores in the placebo group fell 10.06. These reduced iADRS scores indicate greater cognitive and functional impairment.

These differences in iADRS scores were sufficient enough for the trial to hit its primary endpoint with a p-value of 0.04.

While analysts at Jefferies recognised the result as a positive for Lilly and the wider endeavour to treat Alzheimer’s by targeting amyloid, there are more sceptical takes on the data presented, as it is unclear what the narrow statistical improvement in iADRS scores means for clinical outcomes.

Indeed, the results reinforced previously released top-line data that showed donanemab slowed cognitive decline in patients with early dementia symptoms. However, donanemab showed no substantial difference compared to placebo for secondary outcomes, like improvement in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale- Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) and the 13-item Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale, according to the data.

Seeing as iADRS is little used outside of Lilly, the trial’s failure on the well-established CDR-SB hinders efforts to understand what the possible effects of donanemab mean in practical terms for patients.

Lilly is running a second, 500-subject Phase II clinical trial that uses changes in CDR-SB as the primary endpoint, with iADRS serving as a secondary endpoint.

Analysts at Jeffries suspect there is potential for Lilly to frame this Phase II study as a success on the strength of two hits against the iADRS endpoints.

“While FDA [US Food and Drug Administration] considers CDR-SB a regulatory endpoint, we don’t get any sense investors would see a major issue if LLY had two positive studies on iADRS and presumably LLY remains in close dialogue with FDA,” the analysts wrote.

Is Biogen’s aducanumab finally poised for approval?

Based on the data so far, JPMorgan analyst Cory Kasimov said in a note on Monday that Lilly’s donanemab “isn’t yet a clearly superior drug to [Biogen’s] aducanumab”, and that “it’s less likely donanemab is approved early on the basis of these results.”

The somewhat underwhelming results caused shares in Eli Lilly to fall as much as 7%.

This is may not be good news for Biogen’s similar candidate aducanumab. The company previously latched on to Eli Lilly’s positive Phase II data for its amyloid drug as a light at the end of the tunnel for getting aducanumab approved in early 2021.

Biogen’s aducanumab has had a rocky road in clinical development. After positive Phase I/II trials that got the industry hyped by the prospect of a new treatment for Alzheimer’s, the firm halted the drug’s development in March 2019 after yielding poor results from Phase III trials, which caused its share price to plummet. In a surprise twist, in October that year, Biogen announced that it was set to revive its efforts to get FDA approval for the candidate.

Biogen affirmed that new analysis of a larger dataset did in fact show that, when given at high doses, the drug reduced cognitive decline in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease.

However, despite Biogen’s bullish stance on aducanumab’s approval chances, responses from industry analysts and regulatory experts remain mixed and often sceptical. In November, the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee voted strongly against approving aducanumab, based on the strength of existing efficacy data for the drug.

After being bolstered by Eli Lilly’s positive data for donanemab in January this year, Biogen CEO Michel Vounatsos said: “We stand behind the [aducanumab] clinical data, and we continue to believe that the results support approval.”

He added that Biogen is “continuing to engage with the FDA” as it completes its review, and “continue to have very good regulatory interaction, all around the world [for aducanumab]”. The European Medicines Agency is also reviewing a marketing authorisation application for aducanumab, submitted by Biogen and Eisai, Biogen’s long-standing partner in the global development and commercialisation of the drug.

Vounatsos went on to say that Biogen is “ready to launch in the US and we are looking forward to the FDA decision,” which the company expects in early June.

Despite the uncertainty across ‘every data point’ in the Phase III trial, Jefferies analyst Michael Yee said Biogen could still secure FDA approval for aducanumab.

When it comes to drug development, the phrase ‘slow and steady wins the race’ does not apply. The race is on to find a blockbuster disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s and the company to make the breakthrough could reap huge rewards.

Down to the astronomical unmet need and the world’s increasingly ageing population, GlobalData’s consensus forecasts that, if approved, sales for aducanumab in 2036 could reach $5.8bn in the US, and $8bn dollars globally.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding both aducanumab and donanemab, both drugs represent a glimmer of hope in finding a treatment for Alzheimer’s based on the amyloid hypothesis.

“The FDA’s standard of approval usually requires substantial evidence of efficacy and accumulative data for the drug,” says Brunello. “[The data behind] aducanumab is not really exhaustive to meet this standard. However, I think they are likely to approve aducanumab, even if the benefit is modest, because there is a lack of therapies that are truly efficacious to treat Alzheimer’s disease.”

Brunello believes the potential approval of aducanumab is not likely to be the finalised treatment for Alzheimer disease, but could open doors for combined therapies such as beta-amyloid therapies delivered along with anti-tau therapies.

“Combination therapies seem like the way to go for the beta-amyloid inhibitor treatment class,” he says “But the problem cannot be explored until a drug is approved on the markets. The approval of aducanamab can also encourage other companies that failed in the past, for example Lilly’s solanezumab or Roche’s gantenerumab, to re-evaluate their results and try to attract investors to raise money to continue the research.”