Despite the distrust with which the pharma industry tends to be viewed by the general public, it remains an industry that revolves around an overriding social mission. Inventing life-saving products and improving human health is a job for the good guys, after all, and the incredible speed at which novel vaccines and therapeutics have been emerging in response to the Covid-19 pandemic is further proof, if such was needed, of the intrinsic value of a vibrant and competitive research-based global pharma and biotech sector.

The ongoing coronavirus crisis is yet another potent reminder of the deep connections between pharma’s prime social concern, human health, and the world’s changing climate. The Harvard School of Public Health’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment has described the separation of health and environmental policy as “a dangerous delusion”, and while there’s no direct evidence that climate change has influenced the spread of Covid-19, the current pandemic is emblematic of how global warming and its root causes are making the world more vulnerable to emerging pathogens.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

“We of course acknowledge that the health of patients is tied to the health of the planet,” says European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) director of science policy Kirsty Reid. “[Climate change’s] influence on human health can be indirect or indirect – through infectious disease patterns, increasing extreme weather patterns and the risk of drought, floods and subsequent food insecurity, as well as various respiratory diseases from poor air quality. Further understanding of the interface between people, health and the environment is critical. It’s also critical to ensure that the pharmaceutical industry can form and execute our response.”

In 2021, on the eve of another all-important UN climate summit – COP26 in Glasgow – climate change and sustainability is well-established near the top of the pharma sector’s public agenda, from large players joining the drive to net-zero operations to more granular forums such as the Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable, which launched in 2013 to bring together industry figures for pre-competitive discussions on environmental, social and governance (ESG)-related topics.

“The pharma industry, I mean, it’s a bunch of do-gooders,” says Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable co-founder Sandor Schoichet, who is also director of life science-focused Meridian Management Consultants. “Everybody is in this business because they’re concerned about healthcare and science, and the social value of what the industry does. And [the roundtable] was just part of it.”

Taking stock of pharma’s environmental impact

But while the pharma industry of today is replete with ambitious carbon reduction targets and prominent shows of solidarity – GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is one of COP26’s principal partners – there’s evidence that the sector has some way to go before it truly takes stock of its carbon footprint and wider environmental impact.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“The pharma industry appears to have conveniently hid behind its image of clean factories making life-saving drugs,” says McMaster University associate professor of engineering and chair of eco-entrepreneurship Lotfi Belkhir, who has been highly critical of pharma’s approach towards its own carbon impact. “Who cares about carbon footprint when you’re doing so much for humanity, right?”

Belkhir and co-author Ahmed Elmiligi published in the Journal of Cleaner Production a 2019 comparative analysis of the pharma industry’s largest players. Contrary to the industry’s own assessment that it is a ‘medium-impact sector’, the study – which assessed emissions reported by large pharma companies in 2015 – found the industry emitted more, and was more carbon-intensive, than the automotive industry. Specifically, the 48.55 tonnes of CO2 equivalent that the sector emitted per million dollars of revenue was found to be 55% greater than the emissions of the automotive sector.

“We’re needing more and more cold storage, and again this increases emissions.”

The report also found wild variability in the carbon performance of comparable pharma companies – Eli Lilly’s carbon intensity was five times greater than that of Roche, for example – and a lack of transparency on the details of companies’ environmental performance.

“Our main hypothesis is that the pharma industry is so profitable that it can afford to be extremely wasteful in its manufacturing processes and hence has little economic incentive to optimise those high-footprint processes,” says Belkhir.

EFPIA’s Reid questions the “assumptions made” in the 2019 study and notes that some of her organisation’s member companies felt that drawing a line between carbon intensity between pharma and other industries was akin to “comparing apples to bananas”. Nevertheless, she acknowledges that tracking carbon intensity among pharma firms is a challenging endeavour, “given they have so many product types, modalities, locations, the size of their lots, their drug pricing models. This all impacts quite a bit on that.”

Reid also notes that the industry’s hands are sometimes tied by regulations – the ecologically wasteful practice of including paper leaflets with every medicine, for example, is mandated – and that what’s best for proper drug manufacturing and distribution isn’t always what’s best for the environment.

“We need certain heating, certain insulation, and air conditioning as part of the manufacturing,” she says. “This increases emissions, and is something we need to work on. And as we’ve seen recently with vaccines and cold storage – we’re needing more and more cold storage, and again this increases emissions.”

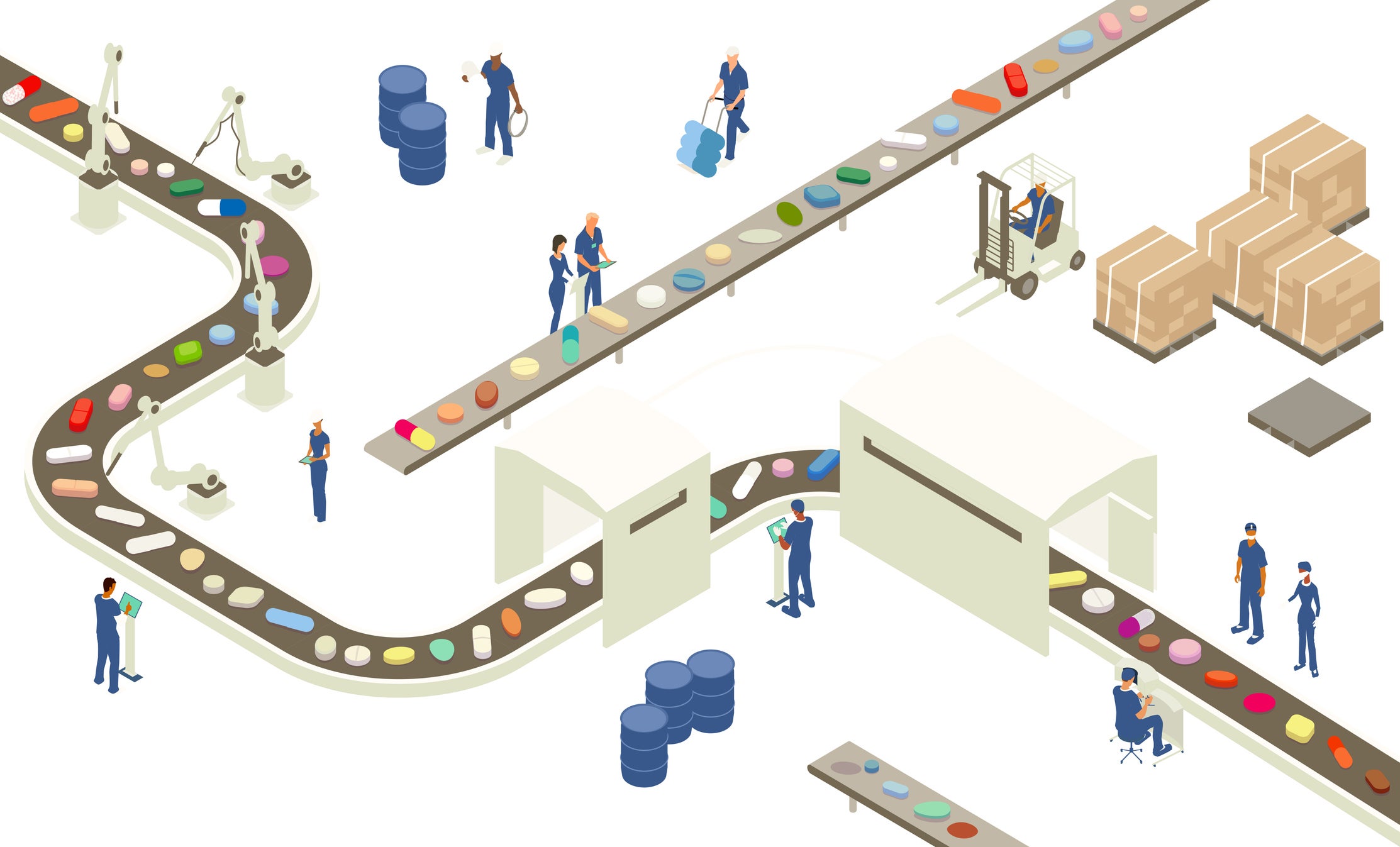

Sustainability in a complex global supply chain

Tracking biopharma’s environmental footprint involves digging through layers of complexity. The breadth of potential impacts beyond simple carbon emissions is huge, from the aforementioned packaging waste, to inefficiencies in transport and logistics, to pharmaceutical contamination of water supplies and drug disposal issues more broadly.

All of these challenges and more are painted across a canvas as wide as the industry’s international supply chain. The globalisation of the pharma supply chain has without doubt saved countless lives as well as dollars, but it has also compounded the challenge of not only ensuring drug safety, but also mitigating environmental impacts around the world.

“The trouble with pharma is that it has so many sub-sectors,” says ESG advisor Myrto Kontaxi, who joined the Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable as a partner in 2016. “No pharma is exactly the same as another, and their supply chains may differ. The pandemic emphasised that global supply chains may have to be rethought in a different way. But you do find very resilient and resourceful people who are in charge of supply chains. And they’ve been challenged immensely over the past two years, in every sector, and specifically the pharma sector.”

While the McMaster study might have cast a pessimistic light on the pharma supply chain and its environmental performance, it’s also true that a great deal of water has passed under the corporate bridge since 2015, the year from which that assessment scraped its data. Emissions monitoring, and environmental stewardship more broadly, is at the core of the business agenda in 2021, pharma included.

“It’s being baked into standards, it’s being baked into regulations, it’s being baked into stock exchange listing requirements, it’s being baked into tender offer structures, and bank loan requests now,” says Schoichet. “At the same time, I might draw your attention to a set of other related things that are more sector-specific. Things like Power Purchase Agreements, where we can decarbonise the electrical supply, because we do use a lot of power. Looking at things like the healthy buildings initiative, which is something that Genentech has been doing. There’s a set of things about resilience because disaster response, it’s not only a business continuity issue in pharma, it’s everybody else who depends on the drugs, right?”

Big pharma puts its green cap on

As the climate emergency has continued to embed itself into the priorities of the business community as well as the public consciousness, pharma companies – like other sectors – have been busy setting targets and collaborating on sustainability initiatives. Reid says “the majority” of EFPIA member companies have made specific public commitments on emissions reduction, often in line with the standards set by the Science-Based Targets initiative. Much of the sector reports its emissions and environmental impacts to the Carbon Disclosure Project to increase transparency with the public. And while EFPIA doesn’t yet make environmental commitments a condition of membership, Reid says “there is a possibility for future consideration of including the environment” in its code of conduct.

On the supply chain side, there have been efforts to wrangle some form of climate action out of an endlessly complex network of clients and vendors. The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Initiative, which was established by industry in 2006, sets standards for responsible supply chain management in terms of safety, social and environmental objectives. Sustainability ratings tools such as EcoVadis, meanwhile, can help businesses in pharma and other sectors to access environmentally responsible supply chain partners while cutting down on manual due diligence.

“It helps with your supply chain because if your suppliers also get their rating, you don’t have to spend so much time doing all the audits and collecting all the materials,” says Kontaxi.

Reid, meanwhile, enthuses about EFPIA’s Eco-Pharmaco-Stewardship initiative to reduce the impact of pharmaceutical products in the environment, as well as its circular economy network and the AMR Industry Alliance, which focuses on the antimicrobial resistance crisis. Even clinical trials are looking to clean up their act through efforts by the likes of the Sustainable Healthcare Coalition.

“The pandemic emphasised that global supply chains may have to be rethought in a different way.”

And on top of the organisations making sustainability in the pharma industry their explicit mission, there’s also the steady market pressure that comes from larger drug companies setting standards for their suppliers – and as Schoichet has observed, it’s often the investors who have set the pace.

“[Investors] were the ones seeing the research on long-term value and outperformance for companies that manage their softer performance aspects more effectively, and pushing it,” he says. “We’ve been creating this work on ESG communications guidance for talking to investors. The investors have found that helpful to share with their earlier-stage portfolio companies, saying, ‘As you grow up, here’s what you should be thinking about.’ Even venture capital people are starting to want to see that as part of the business gameplan for earlier-stage companies.”

The market isn’t pushing for sustainability standards entirely out of the kindness of its heart, of course – as investors have recognised, there’s plenty of evidence that competent environmental management is entwined with a healthy bottom line. “Our current understanding of this linkage between environmental and financial performance is that environmental performance is usually achieved by reducing or eliminating wasteful activities – energy consumption, production waste, transportation, water consumption and so on – which reduces costs,” says Belkhir.

Health implications: pharma’s response to a changing climate

As much as big pharma, as a corporate network with a globe-spanning supply chain, could be described as part of the problem when it comes to climate change, it is also undoubtedly part of the solution – or at least the adaptation. The world’s changing climate is already presenting wide-ranging public health impacts, and the pharma industry is positioned to respond to – and, naturally, profit from – evolving disease burdens and emerging public health crises.

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the value of the industry’s work, from the incredible speed of mRNA vaccine technology to the game-changing potential of the oral antivirals that are now approaching regulatory clearance. But some companies have also been criticised for their monetisation of the coronavirus, and as human rights group Amnesty International has argued, “putting profit before access to health for all” by refusing to share intellectual property.

“That kind of comment from Amnesty is completely unhelpful in the global conversation,” Schoichet counters. “You can’t ship drugs that require cold chain to the middle of a place that has no trained doctors, no hospitals and no refrigeration. There’s been a tremendous amount of work on cross-licensing and production issues to ramp the supply.”

Schoichet adds that social impact, and access to medicines in particular, has been a consistent theme at the Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable. “The conversation has really grown in focus to the social impact issues, like access to medicines and equitable participation in clinical trials, and so on. So that’s where we see the biggest value-add from the industry.”

EFPIA has been working on both climate change mitigation issues – through the CHEM 21 green manufacturing project, for example – and climate-related response plans with the Innovative Medicines Initiative. Reid highlights the Ebola virus epidemic in western Africa as an example of the value of industry collaboration in tackling emerging health threats.

“Under the Innovative Medicines Initiative, we had a call-out for projects on Ebola, and it resulted in two new life-saving vaccines, four new diagnostics and new identification and compliance tools,” she says.

Hopes and expectations from COP26

With COP26 only days away and poised as a critical moment to avert climate disaster, the pharma industry is ramping up its commitments and its messaging on targeting net-zero, a key component of this year’s talks, both for countries and businesses. Summit partner GSK has announced a raft of renewable energy commitments, including a 20-year Power Purchase Agreement involving electricity supply from two new wind turbines and a 20MW solar farm for its Irvine manufacturing site in Scotland, which currently accounts for 40% of UK CO2 emissions from manufacturing.

The company is also taking fresh action on metered-dose asthma inhalers, the use of which represents a stunning 45% of GSK’s total carbon emissions. A lower-emission propellant currently in preclinical testing could, if successful, cut greenhouse gas emissions from inhalers by 90%, GSK said in a late September press release during New York Climate Week.

“You can’t ship drugs that require cold chain to the middle of a place that has no trained doctors, no hospitals and no refrigeration.”

But on the other side of the coin, what are pharma companies hoping to see come out of COP26? Reid describes global climate health equity as a “priority item”, as well as moving forward on science-based targets and promoting a “holistic, global perspective” on solving climate challenges.

Kontaxi emphasises the need for consistency and clarity on regulatory requirements related to climate change and the environment, to avoid the patchwork of regional requirements that currently exists. Whether or not a standard like the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) will become truly global is a key question, because companies need to know if a requirement is going to become a keystone, or merely another thread in a confusing tapestry.

“Greater clarity is certainly something that [pharma] would be looking for,” she says. “And certainty in terms of what’s required, because global companies, not just for climate, have this consistent issue of one region wants this and the other wants that, in terms of regulators and policymakers. And that creates a burden that is not conducive to necessarily becoming better at what you do. It just creates more bureaucracy.”