Agouron Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Pfizer, has pioneered the development of rupintrivir (AG7088), an experimental treatment for the common cold.

Rupintrivir, a synthetic compound, is a member of the protease inhibitor class of anti-viral agents. It is designed to combat colds caused by rhinovirus. This class of anti-viral drugs has revolutionised the treatment of HIV/AIDS and scientists are optimistic that a similar strategy will work for cold viruses.

Following the successful completion in 1999 of initial Phase II trials in volunteers experimentally exposed to human rhinovirus infection, rupintrivir progressed to large-scale Phase II/III trials in patients with naturally acquired colds. Further development of rupintrivir was, however, halted because of a failure to meet the requirements of the Phase II clinical trials.

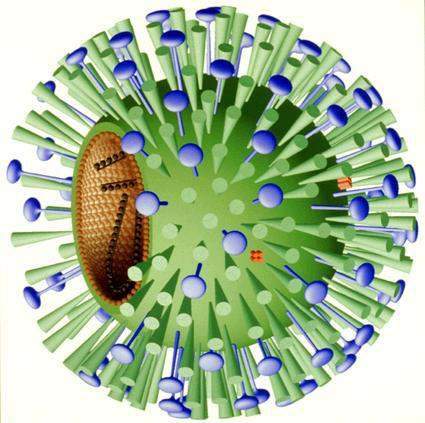

Rupintrivir attacks rhinovirus 3C protease

The 3C protease (3CP) enzyme is central to rhinovirus replication. By binding to and inhibiting this enzyme, rupintrivir prevents rhinovirus replication in cells of the respiratory tract and stops cold symptoms developing.

The drug appears effective against many rhinovirus strains suggesting broad-spectrum anti-viral activity. Because the rhinoviral protease (3CP) is specific to rhinovirus, the drug should have few side effects in humans. Drugs which inhibit these virus-encoded enzymes have a good safety history.

Rhinovirus infection trials

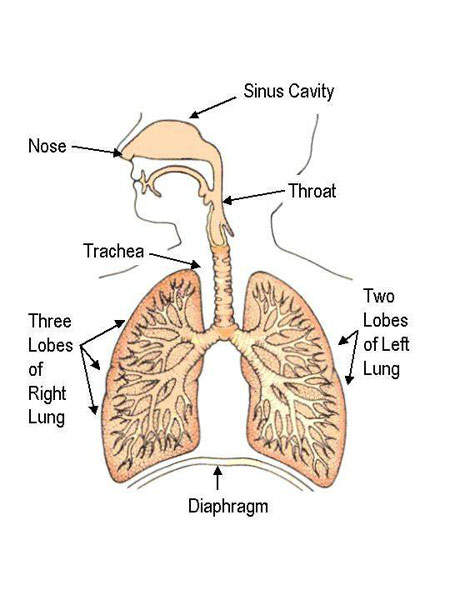

Rhinovirus infection is the most common cause of colds, producing the classic symptoms of a runny nose, blocked sinuses, headache and cough. Rhinovirus infections can be more serious in patients suffering from chronic respiratory diseases, triggering acute exacerbations of asthma, emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

At the end of 1999, evidence from the initial Phase II trial of rupintrivir in volunteers given experimentally induced rhinovirus infection indicated that the drug could significantly improve cold symptoms.

The placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind trial involved susceptible volunteers who received multiple daily intranasal doses of rupintrivir 24 hours after deliberate exposure to human rhinovirus.

Compared with placebo-treated volunteers, those treated with rupintrivir experienced a significant reduction in total cold symptoms, respiratory symptom scores, rhinovirus concentrations in the upper respiratory tract and cumulative nasal mucous production. Rupintrivir was generally well tolerated in this study, consistent with earlier safety data.

These results were sufficiently encouraging to merit investigation of the effects of rupintrivir in naturally acquired rhinovirus infections. A large-scale multicentre trial at more than 50 sites in the US has been initiated. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial intranasal doses of rupintrivir were administered to cold sufferers within 36 hours of cold symptoms first appearing. This trial was be important in determining whether rupintrivir could work rapidly enough following the onset of cold symptoms to meet primary endpoints.

In the Phase II clinical trials rupintrivir demonstrated moderate antiviral and clinical efficacy. Because of a lack of efficacy in natural infection studies further development was stopped. Even the compound 1 that was identified as an orally bio-available inhibitor of 3C protease showed safety and tolerance in Phase I trials but further development was stopped because of marginal pharmacokinetics.

Adapting rupintrivir for treatment of sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

In May 2003 scientists in Germany discovered that the coronavirus implicated in SARS possess similar protease enzymes to those seen in rhinovirus and raised the intriguing prospect that protease inhibitors might be effective against this new disease.

Although Agouron’s rupintrivir doesn’t possess the exact binding-site architecture for coronavirus proteases, with some modification it may be possible to produce derivatives of rupintrivir effective against the cause of SARS. Rupintrivir has been supplied to the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to test on the SARS coronavirus.

Marketing commentary

No commercially available antiviral drugs are yet available to treat the causes of the common cold. Currently available cold remedies provide only symptomatic relief. With the many millions of colds suffered annually, in theory there is a huge market to tap for a successful common cold treatment. However, the therapeutic hurdles are high.

To be effective the drugs need to offer immediate relief and prevent symptoms developing, especially in patients with chronic lung diseases, for whom a cold is not a trivial infection.

Getting anti-viral drugs for the common cold on the market is not easy as the fate of ViroPharma’s Picovir (pleconaril), a rival drug to rupintrivir , illustrates. ViroPharma together with its co-development and co-marketing partner Aventis, submitted a new drug application (NDA) for Picovir in 2002 to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The companies hoped to secure approval to market Picovir for the treatment of otherwise healthy adults suffering from the common cold with a five day, three times daily oral regimen. In August 2002 the FDA rejected the NDA and Aventis subsequently terminated its agreement for Picovir. Rupintrivir has met the same fate.