Tamiflu or oseltamivir is a prescription drug used for prophylaxis and treatment of flu caused by influenza virus types A (H1N1) and B. Oseltamivir was invented and patented by Californian company Gilead Sciences in 1996. Swiss pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche) then purchased the rights to develop and market the drug worldwide under the trade name Tamiflu.

Proven to be effective in adults and children (one year or older), Tamiflu was launched in North America (US and Canada) and Switzerland during 1999 and 2000 and in all major European markets by 2002–2003. The drug is now available in about 80 countries globally, including the US, EU countries, Latin America, Canada, Japan, Australia and Switzerland. In Japan, Tamiflu is marketed by Chugai Pharmaceutical, in which Roche has a majority stake.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initially approved Tamiflu for prophylaxis in adolescents 13 years and older and adults. In December 2005, Roche obtained approval for its supplemental new drug application (sNDA) from the FDA, extending Tamiflu’s prophylaxis indication to patients of one to 12 years of age. In January 2006, Roche obtained a similar approval in Europe.

Roche expanded the production capacity of Tamiflu in 2006 and has since been improving its production volumes to cater to the growing demand for additional supplies of the drug. In May 2009 the company announced that it would be scaling up Tamiflu production to a maximum annual capacity of 400 million treatment courses (4 billion capsules).

Controversy over Tamiflu’s efficacy

Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group’s report released in April 2014 on Tamiflu claimed that Tamiflu is ineffective in fighting with influenza but just provides relief from some of the symptoms associated with the disease. It also claimed that the drug could induce some side effects including renal and psychiatric events, and serious heart rhythm problems.

The report based these conclusions on 46 trials that included 20 oseltamivir and 26 zanamivir (traded as Relenza) studies. The Group, however, also disclosed that many of the studies had design flaws and hence their conclusions could not be definitive.

Roche dismissed the findings of the report and expressed confidence in oseltamivir’s safety and effectiveness in treating influenza.

Efficacy and clinical trials

Tamiflu is found to reduce the duration of influenza illness when consumed as per approved dosage (75mg twice daily for five days). In otherwise healthy individuals the drug reduces the severity of symptoms and infections such as bronchitis. In children it reduces the likelihood of febrile influenza and also the incidence of associated otitis media.

Laboratory clinical studies have proven Tamiflu to be effective against the H5N1 virus in animals infected with the H5N1 strain taken from humans. However, no controlled clinical studies evaluating the drug’s clinical efficacy in people infected with H5N1 are available since human infection with H5N1 strains is rare and geographically dispersed.

Regarding Tamiflu’s effectiveness against avian influenza, anecdotal case reports involving small groups of patients are the only available evidence so far.

These reports suggest that the drug is beneficial when administered within 48 hours of symptoms beginning.

The clinical trials on efficacy of the drug for influenza treatment comprised two placebo-controlled and double-blind clinical trials on adult patients, three double-blind placebo-controlled treatment trials on geriatric patients, and one double-blind placebo-controlled treatment trial on paediatric patients. The trial results in all three categories indicated the efficacy of Tamiflu in treating influenza virus types A and B equally in males and females.

The trials on prophylaxis of naturally occurring influenza involved three seasonal studies and a post-exposure prophylaxis study in adult households, and a randomised, open-label, post-exposure prophylaxis study on paediatric households including children aged one to 12 years as family contacts and index cases. In these trials Tamiflu was found to be effective in reducing the incidences of laboratory-confirmed influenza.

The first case of resistance to the drug was reported by Denmark’s National Board of Health on 29 June 2009. A person who accompanied a H1N1 influenza patient contracted the virus even after Tamiflu was administered for flu prevention. The Denmark case raised questions about Tamiflu’s efficacy in prophylaxis.

Similar cases of H1N1 viruses resistant to Tamiflu were reported in Japan and Hong Kong in July 2009. However, the case reported in Hong Kong was dismissed as the patient was reportedly not administered with Tamiflu. Relenza, Glaxo SmithKline’s prophylaxis drug for H1N1 influenza, could cure the person in the Japanese case, reported UK newspaper The Telegraph.

While the available evidence on Tamiflu’s clinical effectiveness against swine flu is evolving, Roche is conducting more clinical studies to gain further information on the efficacy of its drug against the new virus.

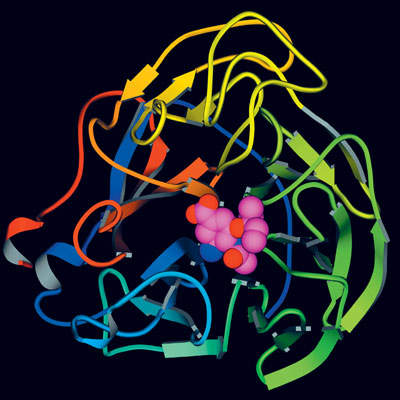

Neuraminidase inhibitors

The influenza virus continues to infect host cells as long as neuraminidase assists the virus in exiting from cells. By inhibiting the neuraminidase enzyme Tamiflu blocks influenza from emerging from the host cells, thus checking the virus spread to other body cells which causes the virus to ultimately die.

This class of medicines called neuraminidase inhibitors are effective against influenza A and B viruses. This is in contrast to the M2 inhibitors, the antivirals that are effective only against the A-type virus.

Marketing commentary

Tamiflu has been found to be active against the new swine flu virus A (H1N1) discovered in 2009, according to the reports from the WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). In April 2009 the CDC even came out with a guidance that has recommended the use of Tamiflu or Relenza (zanamivir) for the prophylaxis and treatment of swine flu.