Academic institutions and commercial entities play an important role in drug development and improving human health. While both types of sponsors are intertwined with each other, a different set of internal and external pressures influence how they conduct research.

While all sponsors are guided by the principle to improve human health, a lot of the investigator-led trials are asking questions that commercial entities do not necessarily want to dive into, says Wendy Tate, PhD, director of analytics and research optimisation at the research compliance solutions provider Advarra. Even if commercial sponsors want to dive into specific scientific questions, they may not have the luxury, she explains.

Indeed, commercial sponsors have to plan within a certain set of business or financial imperatives, and manage their budget tightly to deliver on profitability, says Kenneth Getz, executive director and research professor at Tufts University School of Medicine. They may direct their focus and resources on studies that will yield results and products that can ultimately generate revenue for the company, explains Lisa Sanders, PhD, senior director of regulatory strategy at the CRO Allucent.

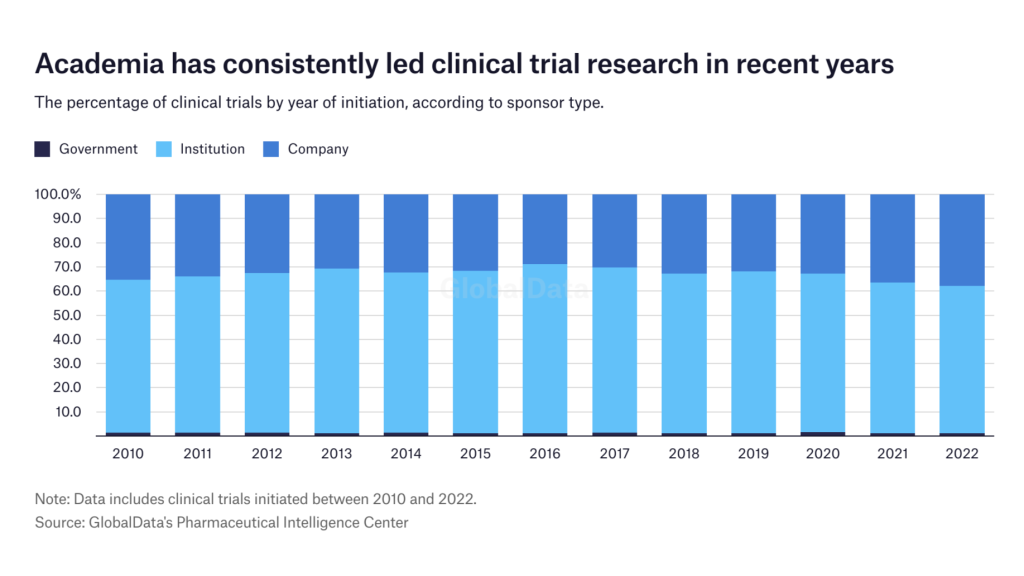

In order to understand the relationship between academia and the commercial sector, Clinical Trials Arena explored how these sponsors are different by conducting a data analysis looking at various clinical trial trends. The analysis shows commercial sponsors conduct fewer but approval-targeted trials, whereas academia initiates more studies that ask wider societal questions. Also, academic and industry sponsors are focused on different therapy areas, which are likely influenced by institutional objectives and market competitiveness, respectively.

Academia initiates more trials

The data analysis shows that academic institutions have led clinical trial research over the past decade. Each year, academia has initiated approximately 60-70% of clinical trials included in this analysis, whereas commercial sponsors initiated around 30-38% of studies.

However, just because academia has initiated more trials, it does not mean that they are all successfully completed. “Registration is one piece of the action, but finishing the trial is another,” says Dr Barbara Bierer, faculty co-chair of the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Harvard and Brigham and Women's Hospital. She explains that commercial sponsors rarely abandon their trials unless it is due to futility, efficacy, or safety concerns. Whereas in the academic setting, if one person leaves or funds are lost, the study may not continue.

Geographically, a different leading sponsor type may be more prolific in each region. Company-sponsored trials are mostly initiated in Europe, Australia, North America, and South America, whereas institution-led trials are more common in Africa and certain parts of Asia. The US has almost an equal amount of both commercial and academic sponsors.

This analysis relied on an exclusive taxonomic approach, which involved the review of thousands of public drug trial records from 2010 to date, as curated in the Clinical Trials Database by GlobalData, the parent company of Clinical Trials Arena.

Varied interest in diseases

When it comes to exploring the type of questions that trials can answer, academic institutions tend to target a wider spread. Tate says a medical school trains upcoming doctors across all different disease realms and has an infrastructure to cover all specialities, whereas commercial sponsors may not afford to run trials in every single disease space.

The analysis shows that academic institutions conduct most of their trials in central nervous system (72.5%) disorders, oncology (69.4%), and cardiovascular disease (69.2%). In contrast, commercial entities initiate most trials in dermatology (47%), respiratory (44%), and immunology (42.5%).

However, academic institutions are often reliant on external agendas and funding. Tate explains that if there is a particular interest in a disease in a country, it is very likely that academic organisations will also be dedicated to that indication. For example, the US federal government oversees a lot of biomedical research, with a big focus on oncology. This interest is not only fuelled by the US National Cancer Institute but also has dedicated support from President Biden’s office, she adds.

Historically, commercial sponsors were keyed into the lifecycle management of the drug, Getz says. Factors such as market crowdedness and protection, as well as the commercial potential of developing a drug for a particular disease were weighed and considered. However, now with the Inflation Reduction Act and other pressures, some indications may become less attractive to fund. The Act aims to lower the cost of prescription medicine for more Americans, however, the pharma industry cautioned that the new law would complicate the R&D process as orphan drugs are exempt. “You may see drugs developed in a more targeted or narrow collection of disease conditions,” he adds.

Governmental interest in infectious diseases

Overall, there were not many drug trials initiated by national governments, according to the data analysis. Getz says that governments tend to fund research that might involve tissue or blood samples, as well as a lot of behavioural studies, which were not included in this analysis.

The data shows that infectious disease is an area of interest for governments. There has been an uptick in communication from global bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) on the need for additional research in this space, particularly malaria or other infectious diseases that are passing through water, parasites, or bugs, says Tate.

Due to climate change, there is an emergence of diseases in newer areas that tend to fund more clinical research. It is no longer an altruistic willingness to work on lesser-known indications that affect poor populations, but it is becoming more of a global issue, explains Tate.

Also, the bio-weapon defence angle could be a factor in why governments could be interested in infectious diseases, says Sanders. Certain diseases could be weaponized, or in the case of Covid-19, it can impact large swaths of the population. “From a public health perspective, it makes sense for them to work in that space and try to support therapeutics,” she adds.

Post-approval research led by academia

While both academic and commercial sponsors have a unified mission to do research, for the most part, they work on different kinds of trials. Bierer says that the industry tends to do early-phase trials to evaluate safety and efficacy, which may aid marketing decisions. Academics, at least in the US, usually conduct Phase IV post-approval studies or comparative effectiveness research where they ask more societal questions, she adds.

Indeed, the analysis shows the majority of Phase I trials (58.9%) are conducted by commercial sponsors, while academics tend to initiate Phase IV studies (67.9%).

Additionally, academia tends to have rich datasets as most academic medical centres are affiliated with hospitals, whereas commercial sponsors may not have access to electronic medical records, Tate says. While drug discovery often starts in an academic setting before being sold off to commercial entities, there is a growing interest from academia to conduct formal Phase I trials, she adds.

Apart from a few exceptions, there is less of a regulatory push to mandate companies to conduct post-approval marketing studies. However, Sanders cautions that if such studies shift from academic to commercial settings, there may be a loss of trials that are investigating new diseases or label expansions. “These are doctors treating their own patients, often they are single-site studies, but this is important proof-of-concept work,” she says, adding that there may not be enough information for a commercial entity to take that trial on a larger scale.

Collaborative but complex relationship

Even though academia and commercial sectors have different objectives when it comes to clinical research, they work in symbiosis. Sanders says there is more collaboration and interconnectedness between the two groups these days, while Bierer notes that academics are very much involved in industry-sponsored studies as principal investigators.

Yet, it is a very complex relationship that is rooted in misconceptions. Getz says academics are leery of the for-profit motivations of industry whereas commercial sponsors feel that academia is slow-moving and bureaucratic. There is no easy way to correct such fallacies, but Getz says more education and transparency can engender higher levels of trust.

Still, all is not lost. Getz, who describes himself as living in academia but studying industry-funded clinical research, is inspired by the level of collaboration he sees in both domains. “I wish that we could find a way to address a lot of the tensions that are largely based on misconception,” he adds.