In spite of gains in public health intervention efforts and medicine, tuberculosis continues to burden low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with higher incidence and mortality rates than wealthier nations.

The persistent struggle to reduce the public health impact of tuberculosis in LMICs is exemplified in Brazil, which currently has the 20th highest tuberculosis incidence globally, according to World Health Organization estimates.

In a 2023 study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases journal, Dr Priscila FPS Pinto and colleagues explored the epidemiology of tuberculosis among the contacts of index case household members in low-income settings, a population that has received little discussion in existing scholarship.

The authors’ analysis showed that there was a higher risk of tuberculosis contraction among contacts with a previously infected household member than the general population, with heightened risk among contacts under the age of five and those identifying as an ethnic minority.

GlobalData epidemiologists forecast that between 2024 and 2027, the diagnosed incident cases of tuberculosis in all ages in Brazil will grow from more than 88,200 cases to nearly 89,700.

The adoption of active, targeted tuberculosis surveillance, as suggested by the authors, may temper these figures, particularly among the youngest contacts of infected household members.

Pinto and colleagues conducted a population-level analysis of tuberculosis incidence among the contacts of household index cases using multiple mortality and tuberculosis registries between 2004 and 2018, yielding 168,804 newly infected patients and 420,854 contacts of a household member with tuberculosis.

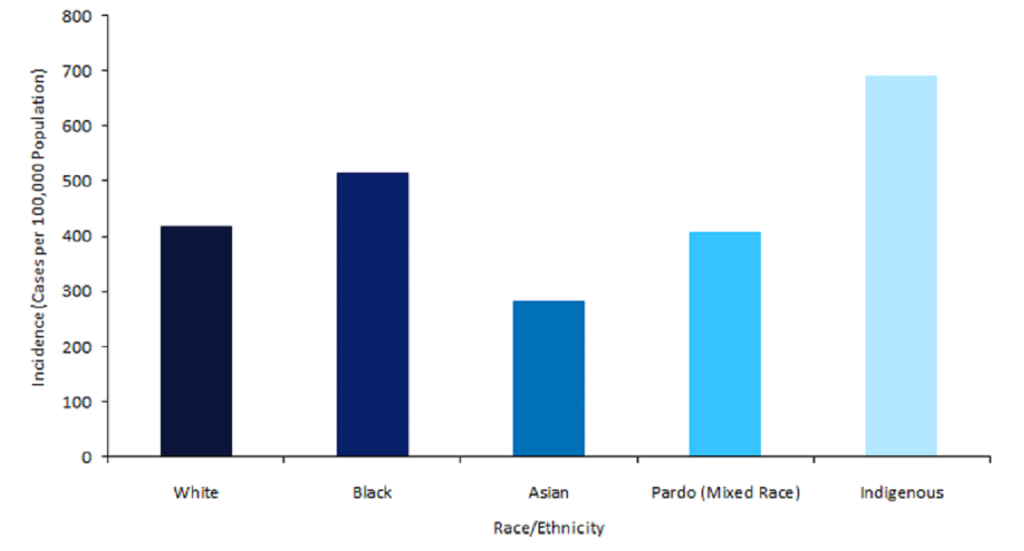

Results showed an incidence of 26.22 cases per 100,000 in the general population compared to 417.8 cases per 100,000 among household contacts.

While these results were consistent with existing research on the risk of tuberculosis contraction, a demographic analysis of these cohorts provided unique insights into the age and ethnic distributions of infected household contacts.

Infected household contacts identifying as Indigenous and Black showed an incidence of 691.3 cases and 514.4 cases, respectively, far exceeding the rates among White, mixed, and Asian peers.

The authors noted another stark disparity among tuberculosis patients under the age of five years, as those in the general population showed an incidence of 4.1 cases compared to 254 cases among those with infected household members.

The authors attribute these stark contrasts to Brazil’s passive model of tuberculosis contact tracing and structural inequities in social policy that increase the risk of contraction among marginalised ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

The large-scale study performed by Pinto and colleagues offers a case study of the complex epidemiology of tuberculosis in Brazil.

The interplay of class and race are historic structural factors behind the risk of contact and infection, emphasising the need for broader initiatives that target social determinants that contribute to inequities in tuberculosis infection.

However, the authors posit a series of reforms in public health practice that could reduce contacts’ infection risk in the household such as monitoring contacts within the first two years of index case infection, providing frequent and comprehensive screening for cohabitants of tuberculosis patients, prioritising contacts under the age of five years, and expanding the public health workforce engaging in tuberculosis surveillance.

These reforms could transition Brazil’s tuberculosis policy to an active model of disease containment, especially among the country’s most disadvantaged groups.

These efforts, paired with broader policies aimed at reducing social vulnerability, offer a path towards significant gains in the fight against tuberculosis for Brazil and the developing world.