Last year, over half of the novel drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were orphan drugs, and the rare disease clinical research field is showing no signs of slowing down. But experts say regulatory incentives for drug reimbursement and support for innovative trial designs would need to be sustained for this significant growth to continue.

The high proportion of drug approvals being related to rare diseases shows that incentives for orphan drug development, like tax credits and market exclusivity, are working, said Karin Hoelzer, PhD, director of policy and regulatory affairs at the National Organisation for Rare Disorders, at a recent clinical trials conference. Popular FDA programs designed to encourage rare disease drug development, like Fast Track designations, Breakthrough Therapy Designations, have been key because they allow biotechs to meet with the FDA to discuss trial protocols, said Akihiro Ko, CEO of a biotech Elixirgen Therapeutics, which is developing a treatment for telomere biology disorders with bone marrow failure. This can be of great benefit for those developing a rare disease drug since it is so case-by-case, he added.

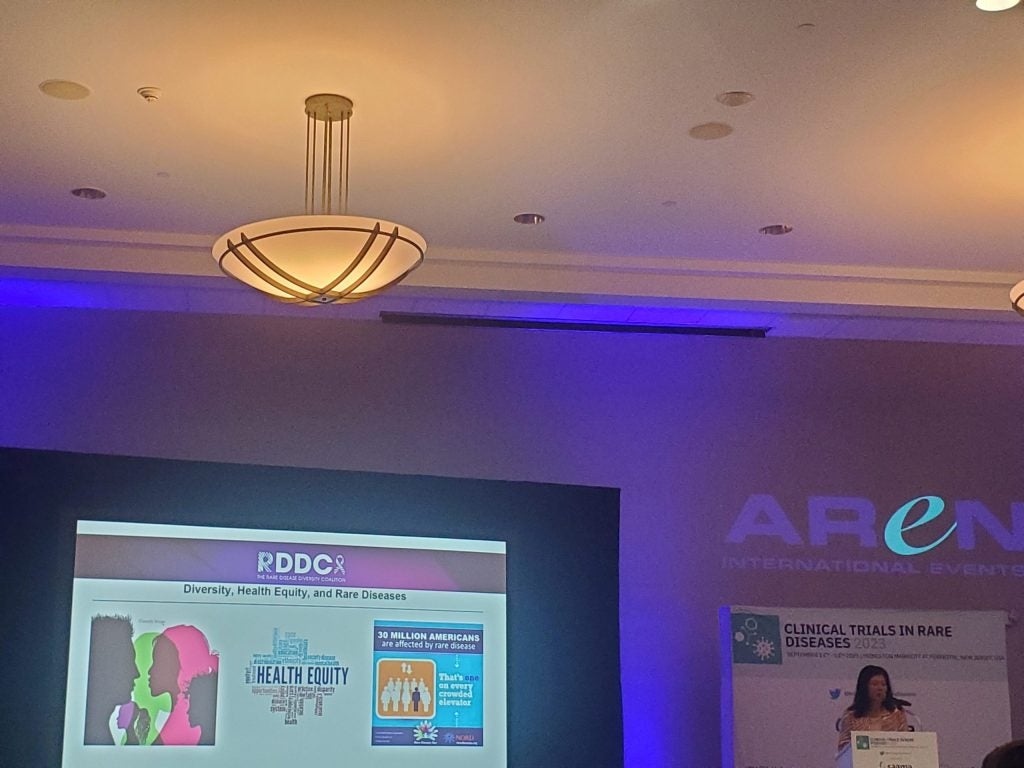

Both Hoelzer and Ko were speaking as part of a panel on what is on the horizon for rare diseases and orphan drug trials at the Clinical Trials in Rare Diseases conference that took place 13-14 September in Princeton, New Jersey.

But a different regulatory action may soon have significant ramifications on the rare disease drug development field in the months to come. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which aims to reduce drug prices among other things, allows for price negotiations for certain drugs on Medicare. The first batch of 10 drugs was announced earlier this month. Orphan drugs are provided an exemption from price negotiations, but this clause only applies to orphan drugs with a regulatory approval in one indication. Hoelzer said such a provision can act as a tremendous disincentive, because the worry is that if companies don’t have the incentive to first bring a drug to market for an orphan indication, they may never bring it to the market later.

Trial recruitment will also be at the top of the agenda for rare disease manufacturers in the coming months. Kristy Galante, senior director, Immunology Janssen Clinical Excellence and Transformation- Rare diseases, described how as part of a large company, which manufactures major immunology treatments like Stelara and Remicade, competition to recruit patients with other drug trials can be a challenge for more common conditions. But with rare diseases, “[we’re] seeing that it requires a lot of education and awareness, which is different from the prevalent diseases that we’ve worked on,” she added.

As the number of rare disease trials grows more than ever before, so does the need to design them smartly. There is a need to devise creative designs that can fulfil regulatory requirements with the FDA while considering the fewer eligible patients. It will take a lot of creativity and courageous discussion with the FDA for this to happen, said Galante. But she was optimistic that trials can be designed using strategies like one to share patient populations across placebo arms, among others.

When it comes to patient-focused drug development, Hoelzer admitted there can be technical challenges in designing trials that measure some endpoints that matter most to patients with rare diseases. But, at the same time the field can continue to push regulators and manufacturers to take appropriate risks to introduce meaningful measures in clinical trials, she added. When it comes to designing trials, Ko said there may no longer be a comparison between rare and prevalent diseases. Rare diseases are increasingly leading the way for study designs, like adaptive ones, and other similar trial designs may become more common across conditions, starting in rare diseases, he added.