Decades ago, regulators and clinical researchers deemed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as the “gold standard” in clinical research, in a bid to shape the lucrative pharmaceutical marketplace. While previously the primary focus was safety, scientific advances allowed them to develop increasingly effective therapies and trials had to keep pace with more established ways to evaluate that. After decades of trial and error, RCTs became the superior method of clinical hypothesis testing.

But can a traditional placebo-controlled, double-blind RCT design from the last century keep up with modern science innovations, statistical and technological advancements, as well as a detailed understanding of diseases in 2023?

How and why were RCTs pinned as the gold standard?

RCTs were only named as “gold standard” in 1982 by Alvan Feinstein and Ralph Horwitz in a paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, the rise of available hospitals allowed researchers to conduct trials. However, with the proliferation of alternate allocation studies, where every other patient was assigned to a different cohort, there was a concern regarding bias introduced by patients or researchers, which resulted in the move from allocation to randomisation studies. While the first conventional notion of an RCT dates back to 1948, this trial design was rarely utilised in the 1950s due to logistical, ethical, and financial challenges.

During the same period, or the “wonder drug” era of antibiotics, steroids, antihypertensives, and antipsychotics, there was a concern that new drugs were entering the marketplace based solely on marketing, says Dr Scott Podolsky, professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School. At the time, there was no mandate by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prove drug effectiveness in addition to safety, even though this was implicit in those evaluations, he says.

In 1962, the Kefauver-Harris Amendment set the stage for the clinical trial infrastructure existing today, by mandating that drugs had to be approved based on the data from well-controlled studies. In the following eight years, the FDA worked to implement the new amendment and defined a well-controlled trial as a placebo-controlled, double-blinded RCT, unless sponsors had an ethical reason not to use a placebo as a control.

To investigate the effectiveness of drugs first marketed before 1962, the FDA formed Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) in 1968. A court case involving UpJohn’s then-popular and profitable Panalba ended with the judicial system finding in favour of the FDA in 1970. This verdict and the US Supreme Court endorsement of the amendment in 1973 cemented not only the FDA’s ability to shape the marketplace but also allowed RCTs to rise to the top of the methodological hierarchy.

What are the benefits of conducting RCTs?

In the following decades, RCTs became a highly regarded methodology to identify effective drugs that provided a rational basis for using medication or any intervention. “This is the best way to evaluate therapeutic efficacy in an empirical sense,” Podolsky says.

Compared to other designs, such as in vitro, animal, retrospective studies or even theoretical expectations, RCTs are deemed more valid in adjudicating differences, he adds.

Also, RCTs eliminate a lot of the confounding bias that can be found in observational studies, says Dr Ben Saville, director and senior statistical scientist for Berry Consultants. “When you want to show causal effects, it's the only mathematical way to simplistically and effectively prove a cause-and-effect relationship,” he notes.

What are the limitations of RCTs?

Even though RCTs are pinned as the “gold standard”, they still pose certain limitations to clinical trial sponsors.

Because RCTs are conducted in a well-controlled environment, they might lack generalisability. Podolsky explains that it can be questionable if events within the confines of a careful study are applicable in the real world.

Saville adds RCTs can also be quite expensive as they require large sample sizes to demonstrate a causal effect. While it might not be a hurdle for big pharma companies, it can be challenging for small investigators or academic institutions.

A data analysis conducted by Clinical Trials Arena reveals that Phase III trials are most likely to be double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs (40%), followed by Phase II (26%) and Phase I (17%) trials, according to GlobalData’s Clinical Trials Database. This is most likely due to large sample sizes in late-stage trials that would allow randomisation.

GlobalData is the parent company of Clinical Trials Arena.

Moreover, RCTs can pose ethical questions. For instance, Podolsky says there can be ethical concerns over withholding a remedy in favour of the placebo, due to the trial design, even after the drug is thought to be effective.

Does the therapy area matter?

In addition to logistical, ethical, and financial limitations, certain diseases do not lend themselves to placebo-controlled RCTs. Some might not have sufficient patients for randomisation, says Saville. In addition, there may be pushback from patients themselves to participate in a placebo-controlled RCT for fear of receiving a placebo rather than the investigational treatment.

While the proportion of placebo-controlled RCTs is similar across various therapy areas, the data analysis shows that only 7% of oncology trials are placebo-controlled RCTs.

It is important to note that this analysis looked at placebo-controlled and not active-comparator trials. Saville notes that in oncology, oftentimes, it is unethical to administer participants a placebo or no treatment. “If there is a standard of care, then that should be the comparator,” he adds.

Active comparators are also often utilised in psychedelic research. Clinical Trials Arena has previously reported on challenges that investigators face regarding study blinding. Due to psychedelics’ obvious physical effects, participants and investigators can tell if the person received an investigational product or placebo. As such, some trials use the same investigational drug as an active comparator but in smaller doses or utilise different substances that can induce similar physical effects.

What is the status quo of trial designs?

The data analysis shows that the proportion of initiated double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs has declined slowly over the past few years. In 2015, 29% of all initiated trials had this design, but this share dropped to 23% in 2022.

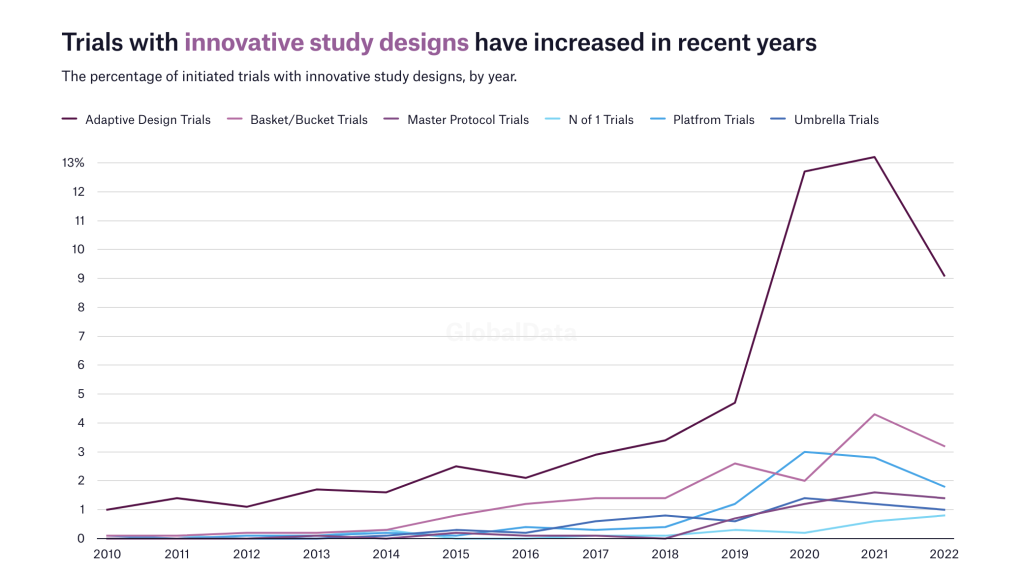

Now, the industry is seeing more innovative and complex trial designs, such as adaptations or multiple interventions with elements of randomisation, Saville says. The data analysis demonstrates that innovative RCT designs such as adaptive or platform trials have been on the rise for the past few years. Also, there has been a rise in trials utilising master protocols, and umbrella and basket trials.

While platform and adaptive designs are also types of RCTs, Saville notes that it makes sense why there is an increase in these designs. “These large-scale clinical trials that we used to do in a single disease are becoming a little bit more difficult because the science is evolving and becoming more complex. We are understanding that there is not just one single type of breast cancer, but there are lots of types of it,” he explains, adding that statistical innovations are also catching up to the innovation seen in science.

Should there be a gold standard moving forward?

When asked about the future gold standard for clinical trials and if there should be one, Podolsky says it is complicated because the industry will always balance the need for information that can help determine whether a drug is effective. “Yet, it's going to be balanced by concerns with ethics of when you can stop a trial, the cost and logistics of doing these trials,” he adds.

Saville says that there should not be one specific type of design deemed as the gold standard as every trial should be custom fit for a particular disease or therapy area. However, he adds that randomisation in trials will continue to be a gold standard, but there will be more innovation in this trial design realm.

He notes that regulatory agencies, such as the FDA, certainly recognise the need for innovative designs. This can be seen in FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) draft guidance agenda for 2023, with several documents specifically looking at master protocols and adaptive trials. Recently, EMA released a reflection paper and invited a discussion around single-arm clinical trials as pivotal evidence for marketing authorisation applications. Saville expects to see more innovative non-randomised clinical trial designs for rare diseases where there can be severe consequences for not administering a treatment to the trial participant.