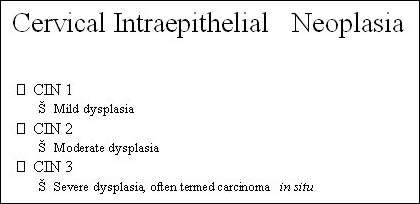

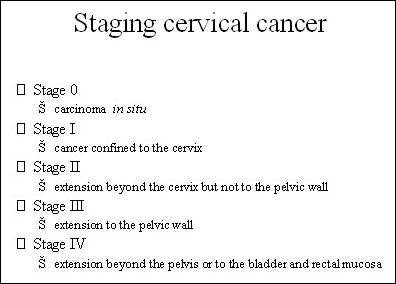

GlaxoSmithKline’s (GSK) Cervarix is a prophylactic vaccine currently indicated for the prevention of precancerous cervical lesions (high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: CIN grades 2 and 3) and cervical cancer associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) types 16 and 18.

GSK filed for regulatory approval in the US in March 2007, at which point the drug was licenced in Europe for use in women aged 10–25 years.

This was met with a “complete response letter” from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) detailing a series of questions that needed to be addressed before it would clear Cervarix for launch.

The company submitted Phase III efficacy study data of the vaccine to the FDA in March 2009; FDA approval followed in October of the same year.

The company also submitted biologics license application to the FDA in 2009 based on this efficacy data.

Targeting HPV in cervical cancer prevention

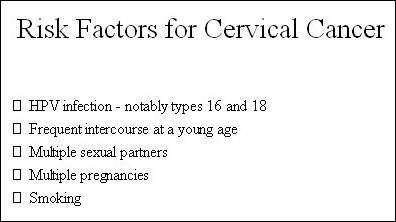

HPV is a common sexually transmitted disease that has been implicated in the development of precancerous cervical lesions and cervical cancer.

Around 100 types of HPV have been identified to date, of which types 16 and 18 are believed to be responsible for more than 70% of cervical cancers that occur in Europe. Most of the remaining 30% of cases of cervical cancer are thought to be associated with other high-risk types of HPV.

Vaccines developed against HPV types 16 and 18 are designed to prevent the acquisition of HPV infection in at-risk females, therefore providing protection against the development of precancerous cervical lesions that may arise from persistent HPV infection and subsequently lead to cervical cancer.

Since many sexually active women contract HPV infection during their lifetime, prophylactic vaccination needs to be given before females become sexually active.

Current immunisation schemes are targeted at children and adolescents who have not yet been exposed to the HPV virus through sexual activity.

Mathematical modelling points to effective prevention

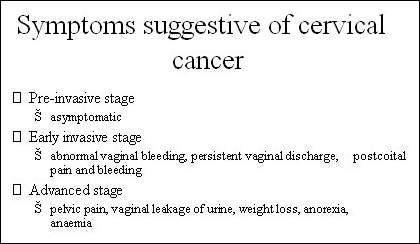

Since it can take many years for cervical cancer to develop, any benefits from prophylactic vaccination will not be seen for a considerable time. However, the number of cases of precancerous changes in the cervix can be expected to fall much more quickly.

Evidence from the Cervarix clinical trials programme involving more than 700 women has shown vaccination with Cervarix to be 100% effective in preventing cervical lesions due to HPV types 16 and 18 in women aged 15–25 years, when followed over a 6.4 year period.

Evidence from mathematical modelling, designed to assess the lifetime clinical benefit of vaccination in cervical cancer prevention, also suggests that vaccination against HPV types 16 and 18 can make a major contribution to reducing the number of cases of cervical cancer as well as deaths from cervical cancer.

With 100% coverage of all 12-year old girls in the US, the model predicted that 70% of cervical cancer cases could be prevented. Even 70% vaccine coverage would achieve a 50% reduction.

Extended study reveals the longest protection by Cervarix

A follow-up study made on women who participated in the Cervarix vaccine’s initial efficacy study has proven that the vaccine is effective for the longest duration than any other cervical cancer vaccine available in the market. Cervarix was effective in neutralising antibodies against the HPV 16 and 18 virus types for up to 6.4 years.

Cervarix goes head-to-head with Gardasil

GSK is hopeful that results of an ongoing head-to-head trial of Cervarix and Merck & Co’s Gardasil will show Cervarix to be the superior of the two vaccines. The randomised, observer-blind study, involving over 1,000 women, is designed to compare the immunogenicity of the two vaccines in young women aged 18–26 years (primary endpoint) as well as in those aged 27–35 and 36–45 years (secondary endpoints).

Cervarix is formulated with the proprietary adjuvant system AS04, which both enhances the immune response and increases the duration of protection against cancer-causing virus types; properties which the company believes may confer benefits over its rival.

In studies, the ASO4 formulation of Cervarix induced higher antibody levels and a more sustained immunological response when compared with a conventionally formulated vaccine with aluminium hydroxide adjuvant alone.

However, Gardasil remains to be the only cervical cancer vaccine that protects against four types of HPV, whereas Cervarix protects against two types.

The Phase III efficacy study of the vaccine was conducted on more than 18,600 women who were in the age group of 15-25 representing 14 different countries. The efficacy of the vaccine in preventing high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN grades 2 and 3) and cervical cancer associated with HPV types 16 and 18 was tested. During the study Cervarix was found to have prevented precancerous cervical lesions in 53% of the patients.

The vaccine is not indicated for pregnant women, but the FDA asked GSK to do post marketing study on the safety of the vaccine in pregnant women as well.

Marketing commentary

After breast cancer, cervical cancer is the second leading cause of death in women in the US, in the 20–39 years age group. Estimates indicate that over 280,000 women worldwide die from cervical cancer each year. While cervical screening has done much to improve early detection and outcome, a vaccine to prevent HPV infection may help to prevent many such cancers developing in the first place.

The vaccine has been approved in more than 90 countries including the US, Mexico, Singapore, Australia, Philippines and the members of the EU. GSK has submitted licensing applications in another 20 countries including Japan.

GSK’s Cervarix competes with Merck’s Gardasil in most major markets around the world.

Immunisation concerns in UK

The UK Government’s national immunisation programme against cervical cancer uses Cervarix, including for girls under the age of 18 years.

The decision to immunise girls as young as 12–13 years has caused much controversy. Given that the virus is only transmitted through sex, some parents felt uneasy that their children had to be immunised at such low age. Adding to this are the fears generated by adverse reactions caused by the vaccine in younger children. According to a report released by the UK government in March 2009, the vaccine caused 1,340 instances of adverse reactions such as nausea, convulsions, fatigue, fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, paraesthesia and myalgia (muscular pains).

However, the UK government has defended the decision, with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) announcing that most of the adverse reactions were in line with expectations and were due to recognised side effects.

The Department of Health and MHRA started the immunisation programme for 12–13-year-old girls in September 2008 and the vaccine will be offered to 17–18-year-old girls during 2010.