Myriad Pharmaceuticals’ Flurizan (tarenflurbil) is a selective amyloid lowering agent under development for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Development of this new anti-amyloid therapy has now ceased following the release of data from the phase III Act-Earli-AD trial that showed Flurizan failed to meet its two co-primary endpoints of improved cognition and activities of daily living in patients with mild AD.

This development will prove especially disappointing to Lundbeck, which had only recently secured European marketing rights to Flurizan (tarenflurbil).

Bridging treatment gaps in AD

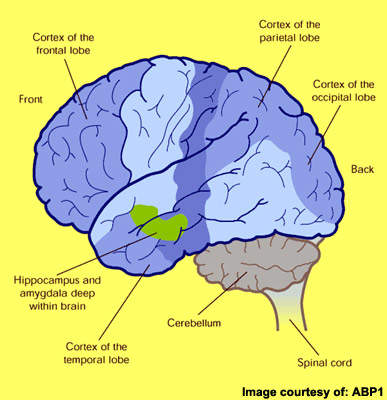

First described by the German physician Alois Alzheimer in 1906, AD is primarily a disease of the elderly. It is the most common form of dementia to affect those aged 65 years and older and is characterised by progressive cognitive decline and accompanying behavioural symptoms.

Despite progress in treatment over the past decade, AD remains an incurable disease. While currently available anti-dementia drugs provide modest symptomatic improvement they do not address the underlying pathology of the disease. Moreover, their effects on cognition, executive functioning and behaviour are only temporary.

None are considered to have disease-modifying effects that can stop disease progression and halt cognitive decline. Many patients also fail treatment with first-line anti-dementia drugs because of poor efficacy, safety and compliance with treatment.

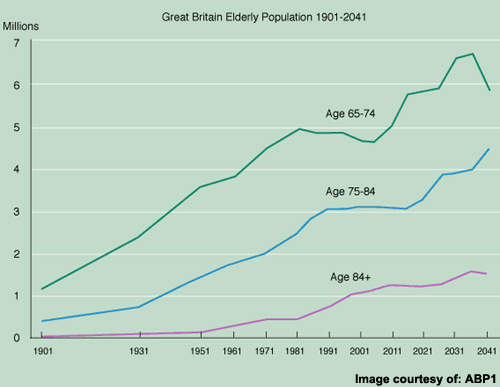

There remains a large population of AD patients eligible for treatment but for whom current anti-dementia drugs are either ineffective or of limited effectiveness. Bridging current treatment gaps is a huge challenge but vital to prevent the inexorable rise in prevalence of AD as the world’s population ages.

Targeting insoluble toxic beta-amyloid

Although the precise cause of AD remains unknown, at autopsy the brains of AD patients show distinctive pathological features of amyloid plaques (sometimes called neuritic or senile plaques) and neurofibrillary tangles.

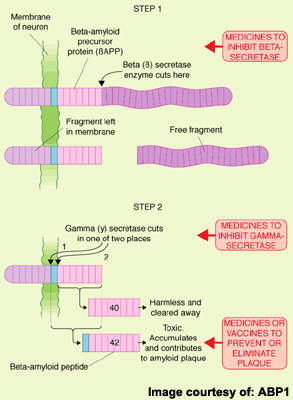

Amyloid plaques arise from the accumulation and aggregation of insoluble toxic beta-amyloid (β-amyloid42) in the brain, which is derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP). This process initiates a cascade of pathological events leading to progressive loss of neuronal function and eventually to the cognitive and behavioural decline that characterises the disease.

Seen as a key pathological event in the development of AD, toxic β-amyloid42 represents an attractive therapeutic target. Several anti-amyloid drugs are in development for AD. They work by modulating the activity of γ-secretase, an enzyme involved in the cleavage of APP to β-amyloid. Preclinical studies suggest they are effective in lowering levels of toxic β-amyloid42.

Flurizan fails in phase III development

On the back of a successful phase II trial, Flurizan (tarenflurbil) progressed to phase III clinical trials, where it was evaluated in about 1,700 patients with mild AD.

The US and global phase III trials evaluated the effects of 800mg twice-daily Flurizan (tarenflurbil) on cognition and activities of daily living in comparison with placebo over an 18-month period. In expectation of good results, patients who completed a full 18-month treatment were likely eligible to continue open-label Flurizan (tarenflurbil).

However, the results showed no statistically significant benefit from treatment with Flurizan on either cognition (ADAS-cog) or activities of daily living. Consequently, further development has ceased.

Results from the earlier phase II study in 207 patients with mild AD showed that the addition of 800mg Flurizan (tarenflurbil) twice daily to ongoing therapy with AChE inhibitors significantly reduced the rate of deterioration in both activities of daily living and global functioning accompanied by a positive trend in cognition, albeit not significant.

.

Marketing commentary

The current market for anti-dementia therapies is in its infancy with among the highest growth dynamics in the CNS market, fuelled by a growing elderly population and the need for better treatments.

Anti-amyloid drugs may have the potential to delay the onset or slow the progression of AD and, if instituted early enough, even stop its development. As such they would revolutionise the treatment of AD. However, none are yet approved for treatment and some promising anti-amyloid candidates have already fallen by the wayside.

Flurizan (tarenflurbil) must now be added to this list, raising further questions about the viability of this therapeutic approach to AD. That said, demonstrating the effectiveness of anti-dementia drugs is also fraught with difficulty given the subjective assessment of clinical efficacy in AD trials.